Armenian Studies Program

Gayane

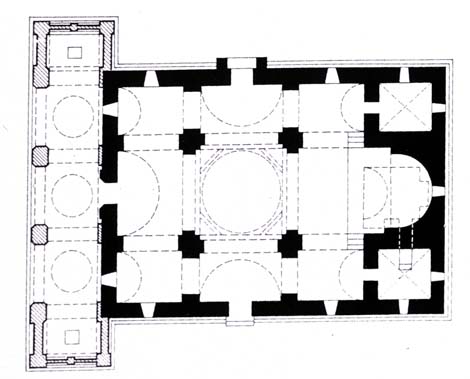

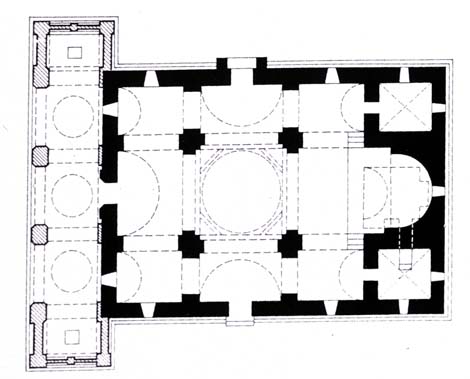

Type: Domed Three Nave Basilica

Location: Province of Ayrarat at Etchmiadzin southwest of the mother church of the Armenians

at Etchmiadzin.

Date: 630-641 AD

Evidence For Date: Erected by the Catholicos Ezr from 631-640 AD

Important details: Located at the site where the Abbess Gayane was martyred

State of Preservation: Excellent condition, in use today

Reconstruction: Khatchkars added in the 11th century, narthex added in the 12th or 13th century,

renovated from 1651-1653, chapel constructed, bema rebuilt and gavit added in 1688

at western end, decorative wall added on entrance in 18th or 19th century, and frescoes

added in the 19th century.

Summary: According to the 10th century Armenian historian Catholicos Yovhannes Drasxanakertc

I, it was erected by the Catholicos Ezr (630-641) at the site where the Abbess Gayane

was martyred by the pagan Armenian King Trdat in the 4th century. The 5th century

Armenian historian Agathanelos describes in the History of the Armenians how Gayane

led the Christian maiden Hrip'sime and her companions from Rome to Valarshapat to

escape the persecution of Diocletian. The subsequent martyrdom of Hripsime, Gayane

and the other maidens led to the conversion of Armenia to Christianity. Tradition

has it that the three sites of martyrdom were revealed to St. Gregory the Illuminator

in a vision in which columns and crosses of light appeared when the Son of God descended

from the heavens and struck the ground with a golden hammer. According to Agathanelos,

one of the commemorative martyria erected by St. Gregory and King Trdat was in honor

of Gayane.

This martyrdom is also mentioned by Eznak, a 7th century Armenian historian, who reports

what the Catholicos Sahak "Repaired it" and "Constructed" one "in stone" in the late

4th and early 5th century. Since the passage could only be interpreted as a reference

to restoration work, the original martrium is still considered to have been erected

by St. Gregory. This "Dak" structure, according to the historian Yovhannes, was demolished

by Ezr in the 7th century to be replaced by a, "Large, brightly-lit structure of stone,"

the present church.

By the early 17th century, the roof of the church had collapsed, leaving just the

walls and the piers, according to Arak'el Dawrizec' I. He reports that the Catholicos

P'Ilippos renovated the church in 1651-1653, including the cupola. A chapel was constructed

under the East apse for the Saint's relics, and the bema was rebuilt. In 1688, an

inscription by the Catholicos Eliazar state that he erected a gavit on the west end.

Beginning in 1872, other restorations were undertaken under the direction of Vahan

Vardapet Bastamean (Alisan, 1890), and later, by Catholicos Mkrtich' Khrimian the

plasterwork of earlier centuries has also been removed.

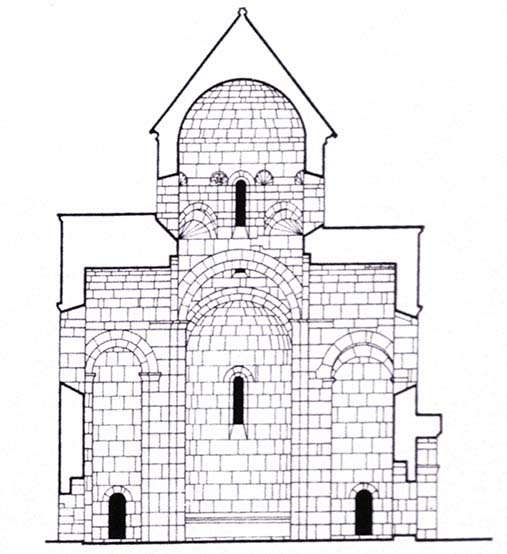

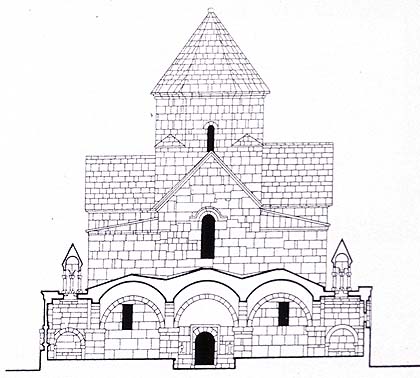

St. Gayane is a longitudinal, cruciform church with four free standing piers supporting

the central cupola. The cross arms radiating from the central bay are vaulted higher

than the four corner bays. These together with the tall drum of the central cupola

give a cruciform appearance to the church from the exterior.

On the interior, the transition from the square bay of the center to the octagonal

drum is made with the use of four squinches. There are eight smaller squinches for

transition between the drum and the dome, as at Mren. The drum is pierced with four

windows, and others are found on the lower elevations, a few with sculptured arches.

The plan represents a synthesis of the three-aisled basilican type found earlier in

Armenia and the central-plan church in which later became widespread there. Gayane

is one of the earliest examples of this type. Its free-standing piers define the cross-in-square

plan found also in the contemporary churches of Mren, Bagawan, and Odzun. However,

its East apse and two flanking chambers are inscribed within the rectilinear exterior

east wall as at Odzun instead of projecting as at Bagawan and Mren.

With its basilican features and central cupola, St. Gayane resembles the earlier type

known from Tekor. In the 11th century, the architect Trdat built the cathedral of

Ani using a similar plan.

The most important innovation in architectural practices of the 6th century was without

a doubt, the appearance and rapid diffusion of the dome, the symbol and material representation

of the celestial sphere. At first, it was constructed in wood faced with stucco, and

later, when it was made of solid stonework, it began to be introduced into the already

existing longitudinal layouts.

Between the 6th and 7th centuries, the presence of the dome was to decisively influence

the formation of ground plans more suitable for containing it, such as the inscribed

cross on St. Gayane's free-standing pillars. The single nave comprising three bays

with a dome over the center and portions of transversal barrel-vaults along the sides

to strengthen the structure which remained in great favor during the following centuries.

The well-known inscribed cross with the dome borne by four free-standing supports

was the basic layout formula for the religious architecture in various Byzantine provinces

from the 9th century onward. Very significantly, this solution had already matured

in 7th century Armenian structures, even though, from the architectural point of view,

the fragility, pictorial approach and grace of the Byzantine solutions (except for

the much-used pictorial decoration) diverged sharply from the rigor and logic of the

Armenian "prototypes."

The view from St. Gayane holds the magnificent Mt. Ararat in its background. St. Gayane

is located only a few hundred feet from the Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, which seats

the Catholicos of Armenia. St. Gayane still remains in perfect condition today. St.

Gayane is being cared for by the people of Armenia and is still used as one of Armenia's

major churches to this day. St. Gayane is a very popular church and is one of the

most active churches in Armenia today.

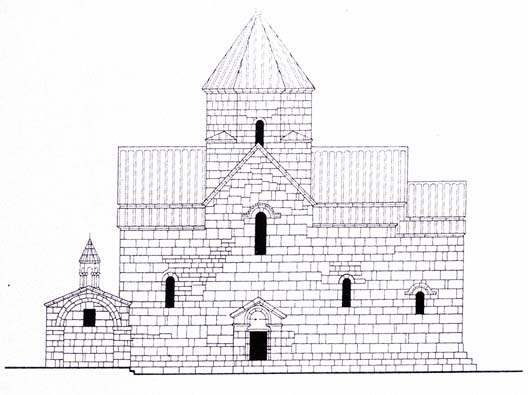

On the western side of St. Gayane, between the 12th and 13th centuries, during the

Medieval Period, a narthex, or covered porch, was added. The narthex was not added

to the original building, but rather a new addition to St. Gayane. Decorative roofstones

were also added to the church. Another addition to St. Gayane came during the 18th

or 19th century. A decorative wall was added on to the front entrance of the church.

The dome of St. Gayane was constructed well and has provided centuries of sturdy support

for the church. The dome has never fallen down and has survived numerous earthquakes.

During the 11th century, khatchkars, or Armenian cross stones, were added on to one

side of the medieval narthex of St. Gayane. The khatchkars were embedded and partially

cut away, giving the appearance of a stone entry way. In the 19th century, frescoes

were added as decoration to the church of St. Gayane.

The narthex that had been added between the 12th and 13th centuries was constructed

of brick and mortar. Much more complex styles of masonry can be utilized when working

with brick as opposed to stone, because brick is a smaller element and it is easier

to work with. Three shallow domes are present in the narthex and there is a keystone

on the entrance.

From the front entrance of St. Gayane, the altar can be viewed, with the Virgin and

Child. The bema has a modern shrine with multi-colored tufa stone that was added in

either the 17th or 18th century. The front of the bema contains a series of crosses,

alternating with a flower pattern that was remodeled in the 17th or 18th century.

Inside the church of St. Gayane, there is a large chandelier, probably dating back

to the 18th century. The style of the chandelier consists of stick shaped glass vessels

in metal loops that were used to hold the oil and the wick.

In the church of St. Gayane, there is a transitional area between arches made at the

free-standing piers. There are also fan shaped squinches that go from one wall to

another.

St. Gayane was constructed remarkably. It remains in excellent condition and is one

of the most beautiful of the early Christian buildings.

Bibliography:

Ep'rikean 1900-1905, 426-428

Lynch 1901, 270-271

Rivoira 1914, 190-197

Clement & Williams 1917, 69-73, 87

Strzygowski 1918, 179-181

T'Oramanyan 1942-1948, 291-294, 125

Jakobson 1950, 41-42

Arutinunian & Sarafjian 1951, 41-42

Sahinyan 1955, 166,168,171,175

Tokarskij 1961, 87-88,101

Mnac'akanyan 1964, 151

Krautheimer 1965, 230

Sarkisian 1966, 208-212

Architettura Medievale Armenia 1968, 87

Der Nersessian 1970, 76, 102-104

Harutyunian 1975, 54-56

Manuc'aryan 1977, 72-73

Der Nersessian 1977 & 1989, 36

Milang 1978, 87-88

Armenian Architecture: IVth-XVIIIth Centuries 1981, 10, 16

Novello 1986, 185-186

Lang & Walker 1987, 14-15

Thierry & Donabedian 1987, 31, 201, 208, 216, 234, 563

Cunneo 1988, 176

Kouymjian 1992, 20-22

-

Floorplan -

Cross-section south wall -

Cross-section interior -

Elevation of south wall -

Elevation of entrance, west -

Gayane -

Gayane -

Gayane - interior -

LGayane