Armenian Studies Program

Churches of Historic Armenia: A Legacy to the World

An Exhibition of Color Photographs by Richard A. Elbrecht and Anne Elizabeth Elbrecht

Presented by the Armenian Studies Program California State University, Fresno

“We know of few countries with a history as turbulent as that of Armenia—ravaged by wars and invasions and occupied by foreign powers—which have left so rich an artistic heritage.” -Sirarpie Der Nersessian

“In their nearly 3000-year history, the Armenians have rarely played the role of aggressor; rather, they have excelled in agriculture, arts and crafts, and trade. Armenians have produced unique architectural monuments, sculpture, illuminated manuscripts and literature.” -George A. Bournoutian

“The history of the Armenian nation does not depend on the written record alone, but is substantiated by a mass of standing remains, ranging from the ancient and medieval capitals to the isolated castles and monasteries which so characteristically mark the landscape.” -Richard G. Hovannisian

“Monuments such as the Cathedral at Ani and the wondrous masterpiece of Aght‘amar are in danger of collapse through neglect.” -Dickran Kouymjian.

Christianity and the Church Edifice

“Armenia architecture is essentially that of church buildings; thus it is a Christian architecture.” -Dickran Kouymjian, The Arts of Armenia, 1992

“The church edifice is the privileged place where Christian mysteries and Christian life find their full expression.” -Boghos Levon Zekiyan, The Ecclesiology of the Early Armenian Church, 1982

“A Christian church is essentially a mirror of the heavenly kingdom, with Whose worship its worship is one.” -Jocelyn M C. Toynbee, Architecture and Art in the Graeco-Roman World, 1969

“In touch with the East and with the West, Armenian architecture drew its inspiration from both sources and served as a link between them.” -Sirarpie Der Nersessian, Armenia and the Byzantine Empire, 1947

“Temples of worship and the images that fill them are first of all documents of the history of religion. Until we have grasped their spiritual dimensions we have not begun to account for them on their own terms.” -Thomas F. Mathews, Art and Architecture in Byzantium and Armenia, 1995

“The Church becomes a true Church only when she remains faithful to her God-given mission, namely, by spreading and translating Christ's Gospel.” -His Holiness Aram I, 1997

Acknowledgments

The captions to the photographs in this exhibition are based on the studies of scholars whose names and publication dates follow each caption. Without their contributions, the identity, history and significance of the churches would not be known or understood. We thank the named scholars and others who have helped us identify monuments and uncover their history. These include T. A. Sinclair, Patrick Donabédian, Dickran Kouymjian, Robert Hewsen, Richard Hovannisian, Claire Mouradian, Keram Kévorkian, Raymond Kévorkian, Christina Maranci, Armen Aroyan, Peter Cowe, Steve Sim, Lucy Der Manuelian, Jonathan Varjabedian, Gabriella Uluhogian, Shushan Yeni-Komshian Teager, the late Vahe Oshagan, and the late Vazken Parsegian. Responsibility for selecting and presenting the data is ours.

The history of the photographed churches - their design, construction, use, neglect, preservation, and restoration - is still being written as scholars and those involved in preservation and restoration carry on their work. The purpose of this exhibition is to aid in educating the public and to inspire continuing scholarship and on-site work. On-site projects (some of which have begun) include resumption of archaeological work at Ani, interrupted by World War I, and restoration of the Cathedral and churches at Ani, the churches at Khtskonk, Varak and Kizil Kilise, and the Church of the Holy Cross on Aght‘amar Island in Lake Van. These churches are treasures of humanity, and future generations will honor those who care for them.

Richard and Anne Elbrecht

Davis, California

March 2008

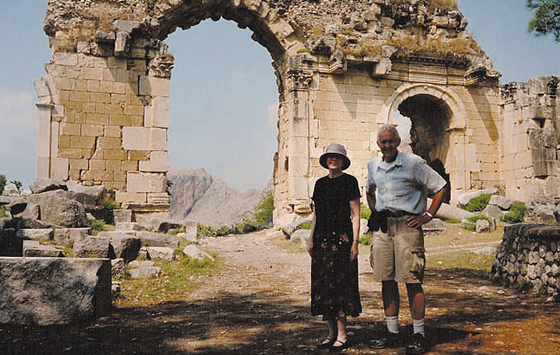

Photo: Anne and Richard Elbrecht in front of the walls of the first-century city of Anazarbus, situated below the 12th-13-th century Armenian fortress of Anavarza. Courtesy Richard Elbrecht

A 1987 vacation to Turkey was the start of twenty-year odyssey, which has taken Richard and Anne Elbrecht on what has become a lifetime passion—photographing and documenting Armenian churches in historic Armenia.

That passion to photograph and document was not meant only for the Elbrechts, who have generously displayed their photographs at a variety of exhibitions and conferences across the United States. The Elbrecht’s decided to donate their entire archive of photographs to the Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno. Their dream was for the photographs to be the centerpiece of a website, which can be shared with the whole world. The first part of the dream, the digitalization of the photographs, was completed at Fresno State, under the direction of University Photographer Randy Vaugh-Dotta. The result of these and their many other adventures in historic Armenia is an exhibition of Armenian churches and monasteries and their natural environments to which the Elbrechts have given the name, Churches of Historic Armenia: A Legacy for the World. The exhibition has been presented at seventeen venues in California and is now being presented to the world by the Armenian Studies Program of California State University Fresno on its website at armenianstudies.csufresno.edu.

The 157 photographs that make up the exhibition were made in tourist visits to Turkey during 1987 through 2007. Most are churches are identifiable by their circular drums and conical domes (where those identifying features have not collapsed in earthquakes). The exhibition is artfully designed and presented. The photographs were made by large-format cameras, and the images are detailed, brightly colored, and expressive of the reality and spirit of the photographed churches and their magnificent natural surroundings. The photographs of the church interiors were made using extra-wide-angle lenses that display more than the unaided eye can see. The images are accompanied by captions providing historical information and viewpoints amassed by scholars.

When asked about why they made their donation, the Elbrechts said, “Some of the churches were built as early as the seventh century and many were built during the ninth through thirteenth centuries, while others date from the nineteenth century. They are tangible evidence of a regal nation that long predated the eleventh-century invasions of Turkic peoples from the east. Some of today’s occupants of the Armenians’ historic homeland are not aware of the Armenians’ long presence in the lands that they now call their home. The photographs also provide meaning to the many historical accounts, and help promote a deeper understanding of the elusive and plaintive history of an extraordinary people and their relationships with those about them.” The photographs, which have been organized into an exhibition, will be of interest to many people of all ages. “The exhibition will intrigue children, who may ask when and why the churches were built, for how long were they used, and how they are being used and cared for now. The exhibition will also interest scholars of art, architecture and religion, who can examine details of church design and decoration not readily accessible elsewhere. The exhibition will appeal to almost every person of Armenian descent for its illumination of an important part of their historical roots. The exhibition might also interest the peoples who occupy the same lands today, since the churches and their use as places of worship form an important part of their history too,” said the Elbrechts. That first trip by the Elbrechts to Turkey in 1987 included not only the obligatory sights of Istanbul, but also a trip on public buses to the eastern part of the country to see the “real Turkey.” There they chanced upon the magnificent medieval church of the Holy Cross on Aght‘amar Island in Lake Van. Built in the tenth century by an Armenian prince, the church of the Holy Cross is considered an architectural marvel, its exterior walls covered with intricate carvings of scenes from the Bible and Armenian history. Although the church is located in an area of major earthquakes, little had been done to shore up its thousand-year-old walls. Two hundred fifty miles north of Aght‘amar, the city of Ani, with its world famous cathedral and numerous churches, lies in ruins, damaged by recurring earthquakes and also by repeated invasions of the Seljuks, Turkmens and others. Upon returning home, the Elbrecht’s wondered what other Armenian churches could be found in eastern Anatolia, and whether identifying, locating, and photographing them might in some way promote restoration efforts. They began to comb scholarly publications about Armenian architecture, and learned to their amazement that there were hundreds of Armenian churches still extant in Turkey, some built as early as the seventh century. Often located atop the highest hill in the area, most were rarely visited. Someone, they felt, had to photograph these monuments before they disappeared altogether. After several days of thought, they decided it would be them.

Each of the nine trips they have made since then has included surprises. A typical example was their attempts in 1996 to reach the Armenian churches at Horomos and Mren. Horomos is located on the Turkish-Armenian border about five kilometers northeast of Ani. Relying on their roadmaps and the copies of the scholarly publications that they brought with them, they took an unpaved road, hoping to find a trail that would lead to the church. At the end of the dirt road stood a military base with a sign reading “DUR” (STOP). “Tour-ist, tour-ist,” we said, hoping to get a friendly response from the officers who came running over to our car. One of the Turkish officers spoke English well. Horomos, he said, was off limits and could only be reached by helicopter. But, in typical Turkish fashion, he invited us into his office for tea. It was, he explained, a very lonely posting. The soldiers weren’t allowed to leave the base during their entire tour of duty, even to go to nearby Kars for a movie. “We stay here,” the young officer said. Horomos, we quickly decided, would have to wait until the border zone was opened.

But could we get to Mren, the location of another intact church, built in the seventh century about fifty kilometers southeast of Ani? We called an Armenian friend in Los Angeles, who leads tours of Armenians to Turkey and knows Turkey well. Hire a taxi driver, he suggested. So the next day our hotel located an obliging taxi driver who took Richard to the village of Duzgecit while Anne remained in Kars.

Here again, though, we were confronted by a military roadblock, with the same message, that Mren was off-limits and reachable by helicopter alone. But our intrepid taxi driver was not easily dissuaded. On the way back to the main road, he stopped at a small village whose Kurdish chief invited them into his hut for tea, and after about an hour he offered to transport Richard to the church on the village’s tractor. Mounting the tractor and sitting on one of its fenders with one hand on the camera case and the other holding the tripod and gripping the tractor’s supporting canopy, Richard endured the 45-minute ride across the terrain of rocks and potholes, reaching Mren in time to take the photographs that are presented in this exhibit and returning to Kars before sundown. The resulting photos of Mren – a church with both drum and dome still intact – made the trip altogether worthwhile. At each of the photographed churches, the Turkish and Kurdish villagers who live near the ruins have helped the Elbrechts locate and photograph the churches. The villagers usually identify ruins as those of Armenian churches or homes, and seem to view them as part of their own heritage and to care for them, especially those in use as mosques, museums, or barns. Nevertheless, in some cases, there is evidence of active destruction of churches. The major risks to the Armenian churches in eastern Anatolia at this time seem to be earthquakes and aging. As long as time and health permit, the Elbrechts will return to Turkey to photograph the extant churches – almost all of them edifices of majesty and beauty. Their presence tells the story of the three thousand years of Christian and Armenian presence in the lands where Armenian Christianity first took root far more accurately and persuasively than might be told by words.

It is imperative that the government of Turkey, with active support from the world, allow properly-trained specialists to restore and maintain these monuments – which are indeed Treasures of the World – before they disappear forever.

Almost all of the photographs were made using a Toyo 45A field camera and 6 x 9 cm roll film holders for their films. To help achieve the “complete record” that was sought, all interiors were photographed using wide-angle lenses. These were a 35-mm Rodenstock Grandagon Wide-Angle, a 47 mm Schneider Super-Angulon Wide-Angle, a 75mm Rodenstock Grandagon Wide-Angle. Two others, a 100 mm Rodenstock Sironar-N and a 150mm 150 Schneider Summar, were also used. The film used in creating the exhibit was Fuji Reala, a color negative film chosen because of its low contrast and highly saturated color. This acclaimed film facilitated photographing the unilluminated church interiors and, at the same time, the open skies and surrounding landscapes visible from inside many churches. While many of the classical Armenian church drums and domes remain, many are missing due to earthquakes, leaving the interiors open to the sky. In the case of one tenth century church – Khtskonk, near Ani – the surrounding landscape is visible from inside through missing walls pierced by explosives planted at each of the four corners by vandals.

With the exception of the Armenian churches of Surb Grigor Lusavorich (Saint Gregory the Illuminator) in Kayseri, none of them are currently functioning churches. Most were destroyed in 1915, and some have been destroyed more recently – in the case of the beautiful church of Surb Sarkis at Khtskonk Monastery, by explosives during the 1960s. Most capture the beauty and spirit of the churches and surrounding countryside.

The photographs are organized into the following 20 groups, which suggest the exhibition’s reach and scope: 1. Kars Province; 2. Ani: City of One Thousand and One Churches; 3. Khtskonk Monastery (Beskilise); 4. Cathedral of Mren; 5. Dogubayazit and Mount Ararat; 6. Monastery of Varag (Yedi Kilise); 7. City and Fortress of Van; 8. Churches and Monasteries About Lake Van; 9. Churches at Moks (Bahcesaray); 10. Surb Kirakos Church and Walls of Diyarbakir; 11. Churches of Urfa (Edessa, Sanliurfa); 12. Churches of Cilicia; 13. Fortresses of Cilicia; 14. Cappadocia; 15. Caesarea (Kayseri); 16. Villages surrounding Mt. Erciyes; 17. Kharpert, Malatya, Amasya, Merzifon; 18. Monastery and Fortress at Shabin Karahisar (Koghonia, Koloneia); 19. Churches at Gireson and Trabzon (Black Sea Coast); and 20. Oltu-Penek Valley and Church of Banak.

Anne Elizabeth Elbrecht is a graduate of Wheaton College, University of California Berkeley School of Library Studies, and McGeorge School of Law. She has just completed a lengthy thesis for a Masters of Art Degree at California State University Sacramento. Her thesis examines the reporting of news in the New York Times and the Missionary Herald about the Armenian Genocide. Richard A. Elbrecht is a graduate of Yale University and the University of Michigan School of Law. As an undergraduate, he managed the photographic staff of the Yale Daily News. Both Elbrechts retired from their positions as staff attorneys for the State of California in 2003. Richard A. Elbrecht died in Fresno on May 26, 2008.

Written by Barlow Der Mugrdechian