Armenian Studies Program

Sculpture

A. Stone Sculpture and Relief Carving

Inevitably in a country with an architectural tradition in stone dating back to Urartian times, the craftsmen who so carefully carved blocks of stones for walls, fortresses, and sanctuaries had acquired the skill to sculpt stone as relief decorations for buildings or as independent works of art. Little sculpture has survived, however, from the pre-Christian period because of the excessive zeal of St. Gregory and the newly convert royal court of Armenia in destroying all vestiges associated with earlier pagan religions. The major exception is a series of extremely large carved monolithic stones [ 121] found in various parts of Armenia and often associated with water sources. They resemble large tailless whales. On them are fish-like designs, but they are know as vishap-k'ar, dragon stones. They date from the second and first millennia B.C.

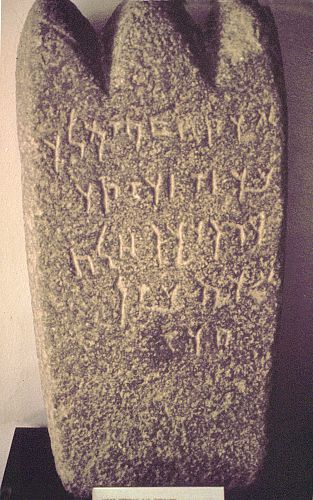

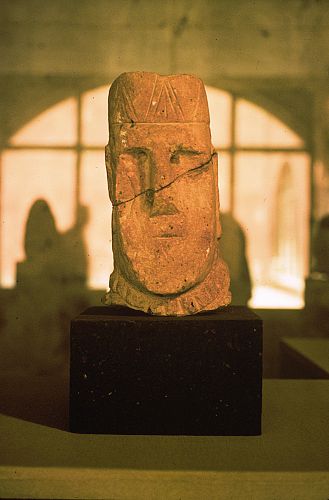

Excavations have uncovered a miscellany of sculptures from the Artaxiad and the Arsacid periods, roughly the second century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. The famous bronze head of Aphrodite [ 216], found at Satala near Erzinjan, now in the British Museum, or the small female torso in white marble dug up at Armavir, testify to the popularity of Hellenistic sculpture in Armenia. Other stone heads [ 123], anonymous but no doubt of Armenian nobility, display a static pose far removed from the classical style. Nearly a dozen boundary markers [ 122] of king Artaxias I (Artashes) from the early second century B.C. have also been uncovered in various areas of Armenia, but these are more important for their Aramaic inscriptions than for their art. The temple of Garni [ 2, 124] from the first century A.D. offers an enormous repertory of sculpted lion heads, acanthus friezes and geometric and floral reliefs associated with the Ionic order of Hellenistic temple architecture.

1. Relief Sculpture

In Christian times relief sculpture on the façades of churches is very abundant [ 4, 10, 18, 36, 52, 54, 130, 131, 132, 134, 138, 139]. Almost all sixth and seventh century churches have carved decorative bands, but some like Ptghni [ 9], Mren, Zvart'nots' [ 17, 128] and Odzun [ 20, 127] have figural reliefs around windows and in the tympana of doorways. The capitals of Zvart'nots' [ 17, 128], uncovered during the excavations of this seventh century monument, are especially elaborate, some carved in a basket style with monograms, while the capitals of the four supporting pillars have enormous heraldic eagles whose wings are wrapped around the sides. Recessed in a niche to the north of the altar at Odzun [ 20] is a finely sculpted Virgin and Child [ 126] in the Byzantine pose known as the "Guide" (Hodegetria). Christ is on Mary's left knee with her cloak wrapped around Him. Her right hand is pointing at Christ. Though this impressive work is attached to the niche, it is carved nearly in three-quarters round, rare for the early Christian period where authorities harbored strong feelings against idols. Relief sculpture, however, was tolerated because it stopped short of recreating the full human form, so important to classical pagan sculpture, and so distasteful to Christian clerics.

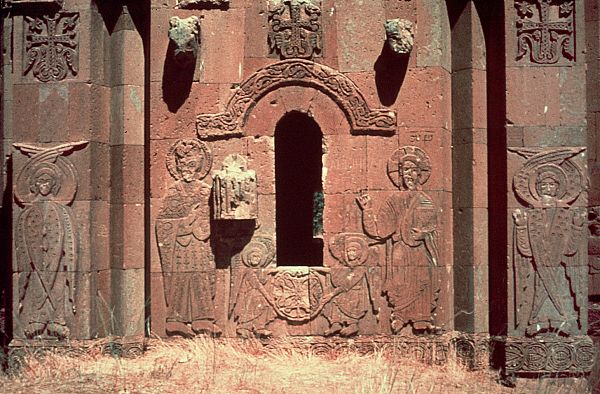

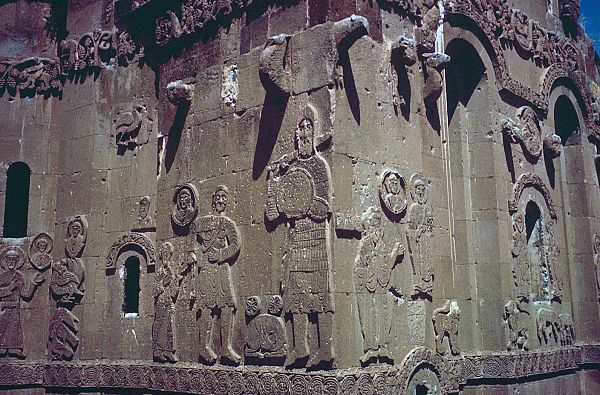

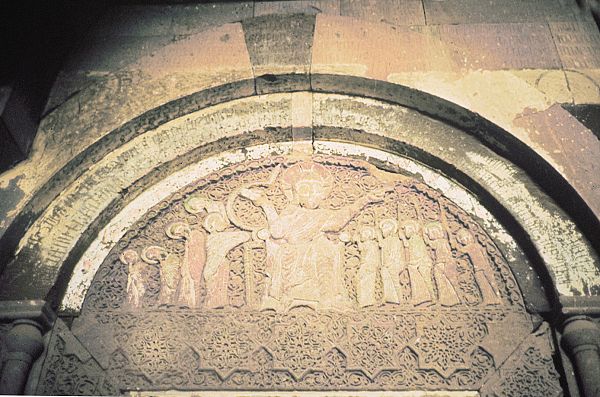

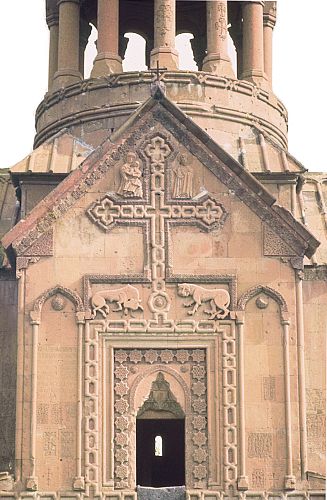

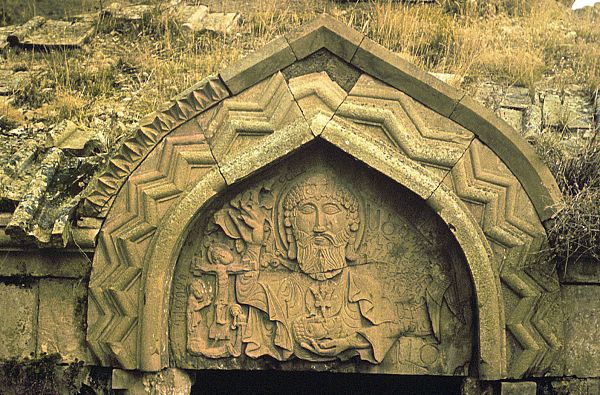

The most famous series of relief carvings in Armenian art are those which cover the entire facade of the tenth century church of the Holy Cross on the island of Aght'amar [ 26, 130, 131]. The church with its external carvings and internal frescoes was built as a palace church between 915 and 921 for king Gagik Artsruni. The unusually deep carving combined with the monumental character of Christ and other figures make this collection of sculpture unique in both Armenian and world art. The sculptures at Aght'amar [ 130, 131] are of a mixed style, with only slight interest in classical forms. The art is very Eastern, very Armenian, peopled with biblical figures in rigid frontal poses. This remarkable façade combines an Old Testament cycle on the major band with a continuous peopled vine scroll above and, still higher, the large individual sculptures of the four Evangelists, one in each of the four roof pediments. Elaborate sculpted scenes on tympana [ 134, 139] above church entrances and on the drums supporting the domes are popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The monasteries of Tatev [ 39], Geghart [ 44, 45, 135, 152, 153], Hovhannavank' [ 46, 134], Haghbat [ 40, 41, 132, 142, 149], Sanahin [ 43, 148], Saghmosavank' [ 47], Makaravank' [ 42], Noravank' [ 52, 139] at Amaghu, Haghartsin [ 51, 33, 37], Kech'aris [ 48], Ts'akhats'k'ar [ 50, 133], and Spitakavor [ 137] are among the most famous. In both quantity and quality, these sculptures represent a very important chapter in Armenian art, one that deserves more attention.

2. Carved Stelae

There is also a large body of free-standing stone monuments in the form of either four-sided stelae or the famous and ubiquitous khach'k'ars. The stelae are found on the grounds of churches; the most famous group still in part in situ is at Talin [ 19, 125]. Some seventy stelae have been recorded. They date from the fifth to seventh centuries; the medium was abandoned as a sculptural form after the Arab invasions. These monolithic stones, often two meters high, are fitted into a carved socle. The tops of some of them are recessed suggesting they were surmounted by a cross. The motifs most frequently represented are standing saints. St. Gregory and King Trdat appear often, Trdat shown metamorphosed with the head of a boar following the story of his conversion to Christianity as known through the History of Agat'angeghos.

The Virgin [ 125] is also frequently depicted as is Christ; crosses or decorative designs are sometimes found on one or more of the four sides. Narrative scenes from the Old Testament -- Sacrifice of Abraham, Daniel in the lions' den, the three Hebrews in the fiery furnace -- are more common than those from the Gospels -- Baptism and the Crucifixion. The iconography of these funerary or commemorative stelae is in keeping with early paleo-Christian models; in style and in the use of certain motifs an Oriental influence is apparent, both early Mesopotamian and Sasanian. Among the most notable of these carved blocks are a very small number that are very tall, reminiscent of obelisks, and mounted on stepped platforms. The most famous are a pair nearly four meters high and enshrined in protecting arches next to the church of Odzun [ 20, 127]. Two or three sides of their faces are carved and separated into ascending panels; pairs of saints, individual figures, and even a short narrative cycle, make up the catalogue of representations.

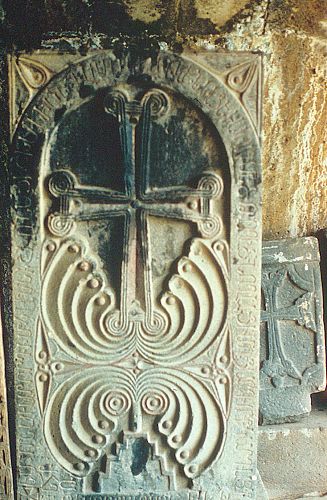

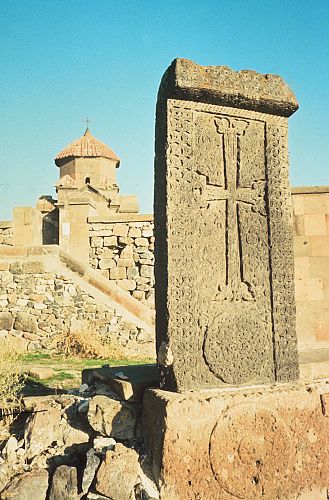

B. Khach’k’ars

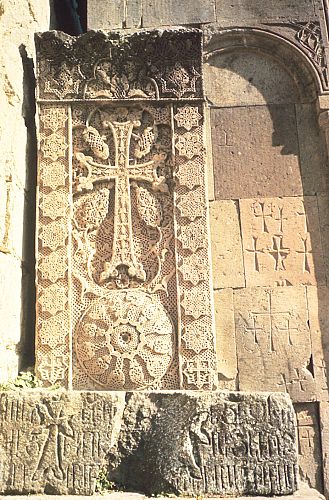

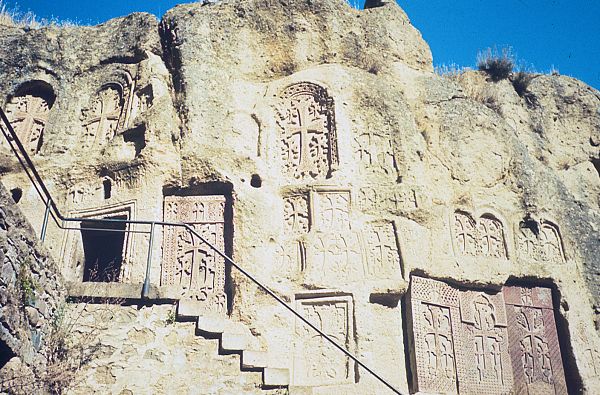

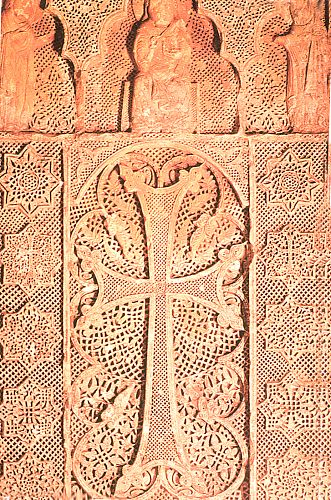

The most characteristically Armenian medium for sculpture was the khach'k'ar, from the word for cross (khach') and stone (k'ar). These free standing, rectangular shaped cross-stones are found everywhere in Armenia; there are thousands of them in all sizes from forty centimeters to two meters high and more. Without exception the central motif is a cross, elaborately and elegantly carved. Smaller khach’k’ars are often found inserted into the walls of churches, for example Hovhannavank' [ 46], and placed at church doorways [ 151]. Like the stelae of the earlier centuries, which perhaps they replaced starting in ninth century, they were used both as gravestones [ 154, 155, 156] and as commemorative markers [ 144, 148].

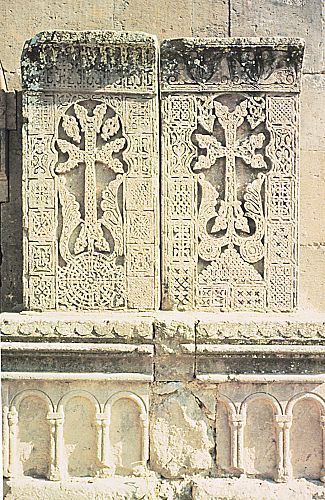

Khach’k’ars were often inscribed with a date [ 141, 142, 146, 149- 151, 153, 155], the name of the person remembered, and at times the name of the artist [ 151, 153, 155]. The earliest examples from the ninth, tenth [ 141] and eleventh [ 142] centuries are usually sober in their design, though often elegant in execution. The cross is always framed by an elaborately carved band and sometimes surmounted by an arch [ 143, 145, 148, 153, 155]. Small carved circles are placed at the corners of the concave ends of each of the four arms of the cross [ 141]; in later centuries these circles are transformed into trilobed foliage [ 151].

Leaves sprout upwards from each side of the base of the cross [ 141, 142, 147] of a khach’k’ar towards its arms; they are usually stylized and in the early period in the form of palmettos [ 142]. This foliage demonstrates that symbolically the khach’k’ar represented the living cross. Its wood is not dead, but alive with new leaves. The cross of the Crucifixion was thought to be made from the Tree of Life, and like the Crucifixion itself, was not a mark of death, but of rebirth through Christ's Resurrection. Without the Crucifixion the Resurrection was impossible; the living cross, the flowering cross, symbolizes the hope of a new life. Because the cross was the sign of the ultimate Christian message of salvation through the Crucifixion and Resurrection, in Armenia it became the most powerful religious image, more prevalent than the Virgin or even Christ Himself.

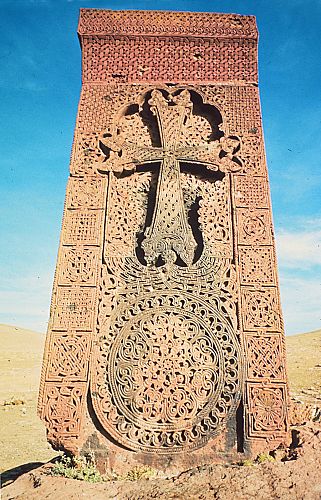

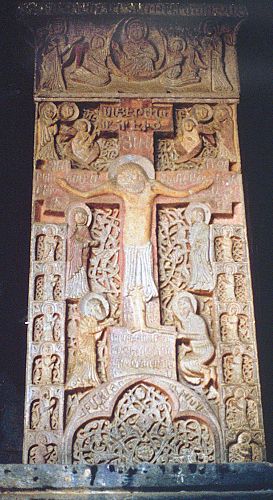

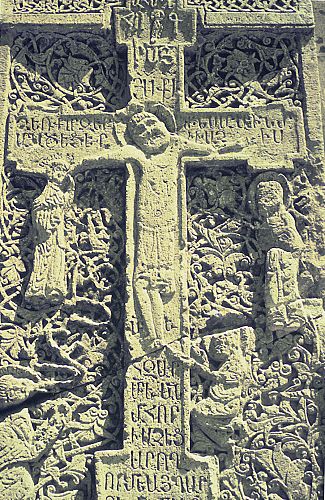

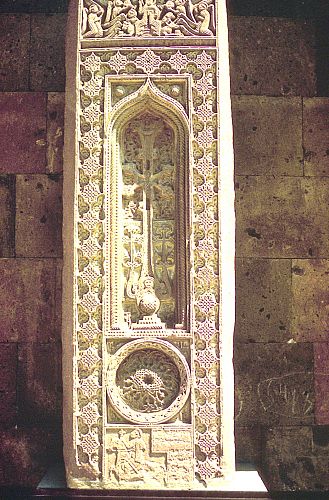

Thirteenth and fourteenth century khach'k'ars were highly ornate sculptural monuments often surrounded by intricate lace-like geometric bands carved on several levels [ 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153]. Many were of monumental size and some were supported by altar-like structures [ 144, 145, 147, 148, 149, 151]. Often they were graced with figural representations. The best known type of the latter variety was the so-called Amenap'rkich' or Savior of All with a fully rendered Crucifixion scene in place of the bare cross [ 149, 150]. The earliest example of this type, one of the most impressive of all khach'k'ars, is dated 1273 [ 149] and is preserved at the monastery of Haghpat.

The best known sculptor of khach'k'ars, Momik [ 153], lived at the end of this thirteenth century; an artist of impressive skill he was also a noted architect and miniaturist [ 97].

Regional styles developed in the carving of these crosses. Artists working in the merchant town of Julfa on the Arax evolved one of the most characteristic types. Practically nothing remains of that city destroyed by Shah Abbas in 1604 except its graveyard [ 154] with its thousands of khach'k'ars, many still standing after nearly four centuries of abandon and neglect in the autonomous region of Nakhichevan now part of Azerbaijan. In the last decade of the sixteenth century Julfan sculptors produced an immense variety of stone crosses, extremely precisely and regularly carved, almost machine made in appearance. The type [ 156] was graced with a decorative band, often of delicate eight-pointed stars, around a complex cross recessed under an ogival niche. Below the cross was an intricately carved rosette and underneath that, the deceased was shown mounted next to an identifying inscription. In a horizontal band at the top, Christ was seated in judgment flanked by angels. Another form of burial stone was a ram carved in the round [ 140], popular in Julfa in the sixteenth century; such ram-stones are also known in Iran and Azerbaijan.

Several of these late sixteenth century khach'k'ars are now preserved in the precincts of Holy Etchmiadzin [ 140, 155]. A more robust style is used on khach'k'ars from the largest extent group in Armenia proper in the cemetery of Noraduz [ 156] on the northeastern side of Lake Sevan. The carving of khach'k'ars has continued into our times, even though they have been gradually transformed into the modern forms of gravestones we see in cemeteries of western countries. The consistence with which these cross monuments were employed is unique to Armenia; the only comparable tradition is the much less developed and short lived one of medieval Ireland.

C. Carved Wood and Ivory

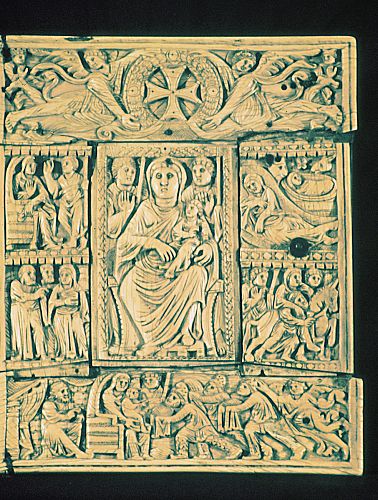

There is a relative paucity of wooden and ivory sculpture perhaps because these materials were precious commodities in Armenia in historical times; furthermore, stone, especially the easily carved tufa, was very plentiful. The most important piece of ivory carving preserved in Armenia is the binding, with upper [ 157] and lower plaques, each in five fitted sections, of the Etchmiadzin Gospels. These were probably carved in the sixth century in a Byzantine workshop and later imported into Armenia. The upper cover shows shows the Virgin with Christ with scenes from her life, including the Presentation of the Magi at the bottom. The lower cover has a beardless Christ in the central panel with scenes from His life.

There are also a number of finely carved ivory bishop's crosiers often with twin dragon heads. Wood was a much more fragile medium than stone or metal and much of what must have been produced has been burned or otherwise destroyed. We know, however, that wood carving was as favored a craft in ancient times as it is today in modern Armenia.

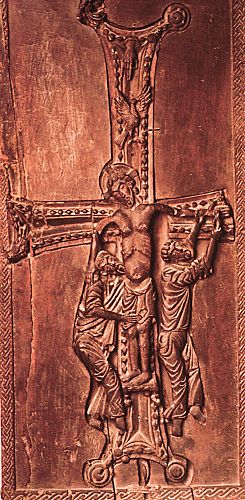

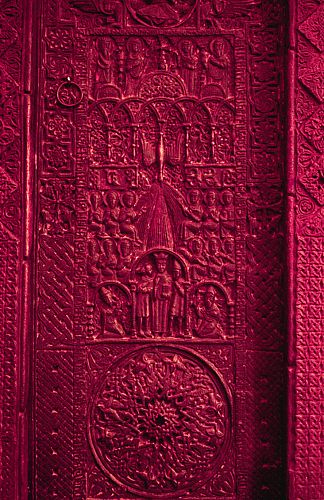

What remains of sculpted or carved wood from medieval Armenia are church doors [ 160], capitals [ 158] used on the columns of a ninth century church, an important carved plaque of the Crucifixion [ 159], and a few miscellaneous items including lecterns. The most important carved wooden doors are dated by inscriptions: 1) 1134, double paneled door, Monastery of the Holy Apostles, Mush, now in Erevan, Armenian Historical Museum; 2) 1176, single panel door, Monastery of the Holy Apostles [ 26], Sevan, Erevan, Armenian Historical Museum; 3) 1253, single panel door, Monastery of Tat'ev; 4) 1327, double paneled door, Church of the Nativity, Jerusalem; 5) 1355/6, double paneled door, entrance to Chapel of St. Paul, Armenian Patriarchate, Jerusalem; 6) 1371, double-paneled door, from Armenian church in Crimea, now in the Hermitage, Leningrad; 7) 1486, single panel door, Church of the Holy Apostles [ 160], Sevan, now in Erevan, Armenian Historical Museum. The borders or frames of all of these are covered with geometric bands or vine scrolls. Those of Mush show mounted warriors at the top either fighting or hunting exotic animals; on the sides there are rows of animals, too.

The fields of the doors are varied: The Mush door has an all over geometric design of radiating eight-pointed stars; the Jerusalem door of 1355/6 and that from the Crimea of 1371 have equal-armed crosses alternating with eight-pointed stars similar to the arrangement of Kashan tiles; those in Bethlehem, Sevan (the one of 1176), and Tat'ev have large crosses carved on them imitating contemporary khach'k'ar designs. The Sevan door of 1486 is in a very separate category. A monumental and magnificently carved scene of Pentecost [ 160] covers the greater part of it; below there is a large rosette similar to those found on contemporary khach'k'ars and on the upper panel, Christ in Glory. The iconography of this panel is perfectly Armenian; its model was no doubt a manuscript miniature.

The oldest examples of sculpted wood are the carved capitals [ 158] from the Holy Apostles Monastery on the island of Sevan [ 24]; they may be contemporary with the building of the church in 874 or slightly later. They are richly and deeply carved with floral scrolls, birds, six pointed stars, and crosses. Several folding wooden lecterns, undoubtedly from churches, are preserved in the Armenian Historical Museum. They date from the eleventh to the thirteenth century and are elaborately carved with geometric designs, birds, and in one case a lion rampant. The single non-functional wooden sculpture that has survived from the early period is the wooden panel [ 159] offered by Gregory Magistros in 1031 to the church of Havuts' T'ar. The panel, now in the Treasury at Etchmiadzin, shows Christ being removed from the cross by Nicodemus and Joseph of Armathea. The simple but delicate carving and the unusually expressive quality of Christ being removed from the cross help to create one of the masterpieces of Armenian sculpture.

The iconography is unique in Christian art, because it incorporates the elements of the Trinity: the hand of God, the dove of the Holy Spirit, and Christ. The panel, regarded by some as a wooden icon, was much admired in the thirteenth century and may have had an influence on khach'k'ars of the period. The craft of wood craving continues to flourish in Armenia. In villages utilitarian items for the household, especially kitchen utensils, are still delicately fashioned. The Folk Arts Museum in Erevan has an impressive collection of nineteenth and twentieth century wood carving. Hand carved gifts of very high quality are also readily available in shops in Erevan.

-

121. Vishapak'ar, "Dragon Stone," ca. 1200 B.C., found on Mt. Gegham, Sardarapat Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

122. Boundry Marker of Artashés I, IInd century B.C., found near Lake Sevan, Erevan, State Historical Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

123. Stone head with Armenian tiara, ca. first century A.D., from Dvin, Sardarapat Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

124. Ornamental carving from acanthus leaf frieze, Temple of Garni, first century A.D., photographed on the site before reconstruction of the temple. Photo: Gulbenkian Foundation Archive -

125. Four sided pedestal for a stele, Virgin and Child with Angels, precincts of the church of Talin, Vth century. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

126. Stone sculpture, Virgin and Child "Hodegetria,", in niche of north wall of the church of Odzun, VIth or VIIth century. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

127. Carved obelisk like stelae with saints, Odzun, VI or VIIth century. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

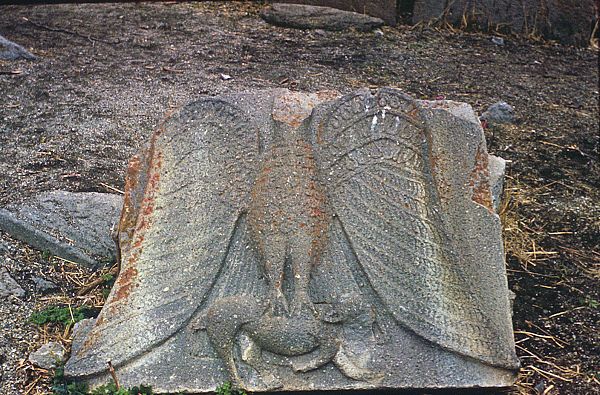

128. Carved eagle capital, originally four, church of Zvart'nots', 641-653, photographed on the site before reconstruction. Photo: Ara Güler -

129. Architect's model for a church, Siunik', VIIth century, Erevan, State Historical Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

130. Relief carving, King Gagik presenting model of the church to Christ, Aght'amar, church of the Holy Cross, West façade 915-921. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

131. Relief carving, David and Goliath, Aght'amar, church of the Holy Cross, West façade 915-921. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

132. Relief carving, Smbat and Gurgén Bagratuni, sons of Ashot III, with model of church, east façade, St. Nshan, Xth century, Monastery of Haghbat. Photo: Patrick Donabedian -

133. Relief sculpture, Eagle and Lamb, Ts'aghats'k'ar, 1041. Photo: Ara Güler -

134. Relief carving, Christ with the Wise and Foolish Virgins (with beards), tympanum of the church of the Virgin, 1217, Hovhannavank'. Photo: Ara Güler -

135. Carved cross on a pedestal in the rock cut interior, 1263, Geghart' Monastery. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

136. Carved tombstone with feline of Elikum III Orbelian, 1300, church of St. Gregory, Noravank' at Amaghu. Photo: Patrick Donabedian -

137. Stone carving, the Virgin, part of a group, 1321, from church of Spitakavor, Erevan, State Historical Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

138. Relief carving, the Virgin detail, South façade, church of the Holy Virgin, 1321-1328., Eghvard. Photo: Ara Gûler -

139. Relief carving, Birth of Adam with God, Adam, and the Crucifixion, late XIIIth century, tympanum of the west façade of the Gavit'-Jamatun, church of St. John, Noravank' at Amaghu. Photo: Ara Güler -

140. Sculptured ram, grave marker from Julfa on the Arax, late XVIth century, now at Etchmiadzin. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

141. Khach'k'ar, 996, from Noraduz, now at Etchmiadzin, Catholicossate. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

142. Khach'k'ar, 1023, Haghbat Monastery. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

143. Khach'k'ar, XIIth or XIIIth century, now at Etchmiadzin. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

144. Khach'k'ar, XIIth century, Karmravor church yard, Ashtarak. Photo: Ara Güler -

145. Khach'k'ars, XIIth-XVIth centuries, Bjni. Photo: Ara Güler -

146. Khach'k'ar, 1211-1212, mounted in a rock, Mastara. Photo: Ara Güler -

147. Khach'k'ars, XIIIth century, church of St. Gregory, Goshavank'. Photo: Ara Güler -

148. Khach'k'ar, XIIIth century, Monastery of Sanahin. Photo: Ara Güler -

149. Khach'k'ar with Crucifixion know as the Savior of All (Amenap'rk'ich') type, 1273, church of St. Nshan, north entrance, Haghbat. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

150. Khach'k'ar with Crucifixion, Amenap'rk'ich' type, 1279, from Tsugingöl, Ayrarat Province, now at Etchmiadzin, Catholicossate Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

151. Khach'k'ar, 1291, sculpted by Poghos/Boghos, Goshavank'. Photo: Ara Güler -

152. Khach'k'ars, XIIIth-XIVth centuries, rock cliffs around Monastery of Geghart. -

153. Khach'k'ar, 1308, sculpted by Momik, from Noravank, now at Etchmiadzin, Catholicossate. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

154. Khach'k'ars, pre-1605 (XVth-XVIth centuries), Old Julfa Cemetery, now in Nakhichevan region of Azerbaijan. Photo: Center for Study and Documentation of Armenian Civilization, Milan -

155. Khach'k'ar of Baron Yovhannés, 1602, from Julfa on the Arax, now at Etchmiadzin, Catholicossate. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

156. Farmer's tombstone, XVIth or XVIIth century, cemetery at Noraduz. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

157. Carved ivory binding, upper cover in five sections of Etchmiadzin Gospel, Virgin and Child with scenes from her life, VIth century, probably from a Byzantine workshop, Erevan, Matenadaran, Ms. 2374. Photo: Ara Güler -

158. Carved wooden capital, from church at Lake Sevan, IXth century, Erevan, State Historical Museum. Photo: Patrick Donabedian -

159. Carved wooden panel with Removal from Cross with Trinity, Xth or XIth century, offered to church of Havuts' T'ar by Gregory Magistros, Etchmiadzin, Treasury. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian -

160. Carved wooden door with monumental scene of Pentecost, 1486, from the church of the Holy Apostles, Lake Sevan, Erevan, State Historical Museum. Photo: Dickran Kouymjian