Armenian Studies Program

Arts of Armenia-Textiles

The serious study of Armenian textiles is still in its infancy. There are scattered monographs and catalogues on Armenian carpets [221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 240], lace and embroidery [253, 254, 255, 256, 257, 259, 260], cloth fragments preserved in manuscript bindings [241, 242, 243, 244], ecclesiastical vestments [251, 254], altar curtains [245, 246, 247], and clothing [258]. However, not one of the rich textile collections in the Armenian monasteries in Etchmiadzin, Jerusalem, Venice, Vienna, and elsewhere is graced by a catalogue or complete inventory.

The complex history of Armenian weaving and needlework was acted out in the Near East, a vast, ancient and ethnically diverse region. Few are the people who, like the Armenians, can boast of a continuous and consistent record of fine textile production from the first millenium B.C. to the present. Armenians today are blessed by the diversity and richness of a textile heritage passed on by thirty centuries of diligent practice; yet they are burdened by the pressure to keep alive a tradition nearly destroyed in 1915, and subverted by a technology that condemns handmade fabrics to museums and lets machines produce perfect, but lifeless cloth.

A. Carpets

The oldest existing tufted carpet, dating from the fifth to the third century B.C., was excavated from the frozen Scythian burial mounds at Pasyryk northeast of the Caucasus in the Soviet Union. Called the Pasyryk carpet and preserved in the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad, this extraordinary rug predates other whole examples by more than 1500 years. The rug is in a near perfect state of preservation; it is roughly six feet square and the predominate color is red-brown. The central design is made of geometric star patterns enclosed in five successive borders, the second of which contains a continuous line of large antlered animals and the fourth from the center, a procession of men mounted on caparisoned horses. Recent scholarship inclines toward Armenia as the place where it was woven, because of the similarity of motifs in late Urartian and some early Armenian artifacts, and the long history of tufted carpet weaving in Armenia.

The Scythians, according to this theory, acquired the rug when passing through the Caucasus. Whether or not the oldest carpet in the world was made in Armenia, early Greek, Armenian, and Arabic historical sources repeatedly speak about the fine rugs and other textiles woven there. Carpets are mentioned as part of the annual Armenian tribute to the Caliph of Baghdad in the late eighth century. In the later medieval period, Marco Polo praises the rugs woven by Armenians. The characteristic red Armenian dye (vordn karmir) was prized throughout the Mediterranean world. Unfortunately, no rugs have survived from these early centuries. There are a few fragments from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, uncovered in mosques in Eastern Anatolia, but no convincing origin has been established for any of them, though Armenia has been proposed for several. However, renaissance artists in the west painted rugs imported from the Near East in precise detail allowing scholars to establish some of the basic designs of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries. Until very recently, scholars have dismissed the possible Armenian origin of these carpets.

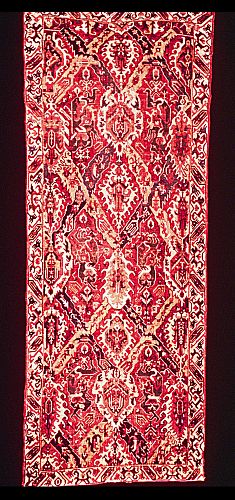

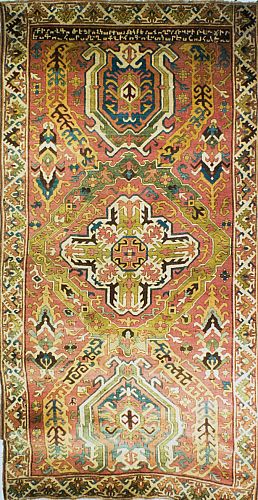

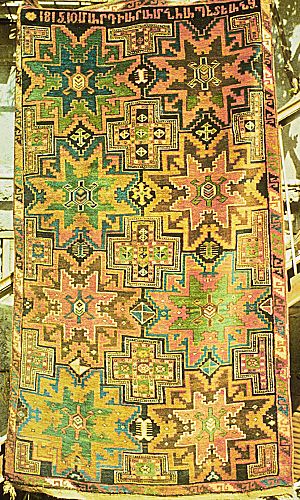

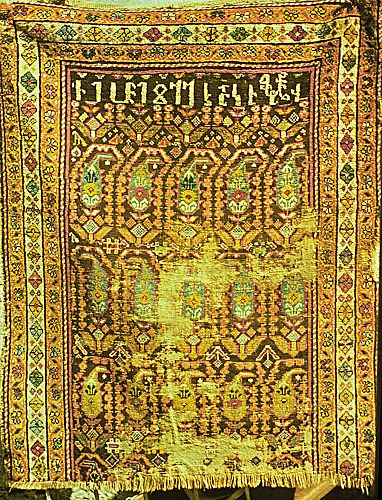

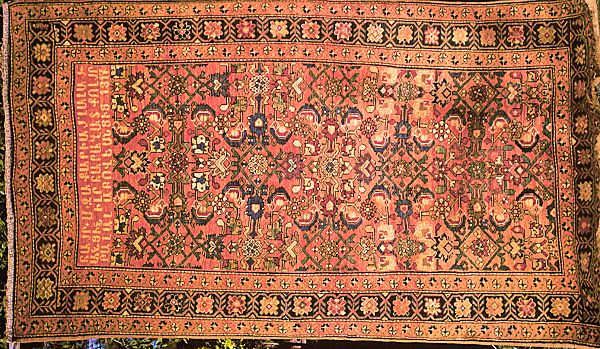

Though there has been much debate during this century on the source of the famous "dragon" carpets, A. Sakisian and others after him propose an Armenian origin for them. The Armenian province of Artsakh (Karabagh) has retained the dragon design into modern times, reinforcing the Armenian origin of seventeenth [221] and eighteenth century examples. A number of these dragon rugs have Armenian inscriptions [222]. During the dislocation of the first World War, the production of Armenian handloomed rugs nearly ended as did that of so many other crafts. Some survivors, however, continued to weave Armenian rugs until World War II [239]. Furthermore, the wholesale destruction of Armenian life and property in Anatolia and western Armenia from 1915 to 1922 resulted in the loss of heirloom Armenian rugs passed down in families.

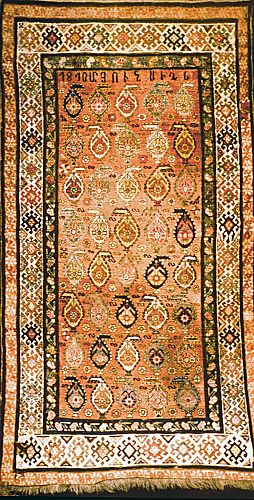

In the last two decades a new interest in Armenian weaving and rug making has resulted in the re-establishment of the identity of Armenian carpets, which in this century have been, unfortunately, gradually subsumed under the heading of Islamic or Turkish carpets. What has helped in the scientific study of the rugs produced by Armenians has been the habit, already remarked upon in other arts, of weavers leaving a written memorial by way of Armenian inscriptions woven directly into the rugs with names and dates [222, 225, 226, 228, 229, 233, 234, 235, 237, 238, 239]. Hundreds of these inscribed Armenian rugs have now been recorded and several major exhibitions organized around them.

The earliest dated Armenian rug is also one of the largest and most exquisite, the famous Kohar carpet [222] made in the Karabagh (the Armenian district of Artsakh) with an inscription identifying the weaver, Kohar, and the date 1700. Another important carpet woven in 1731 for Catholicos Nersés of Aghuank', probably in Artsakh, is preserved in the monastery of St. James in Jerusalem. The rest of the dated and inscribed Armenian rugs are from the nineteenth and the first quarter of the twentieth centuries [225, 226, 228, 229, 233, 234, 235, 238, 239].

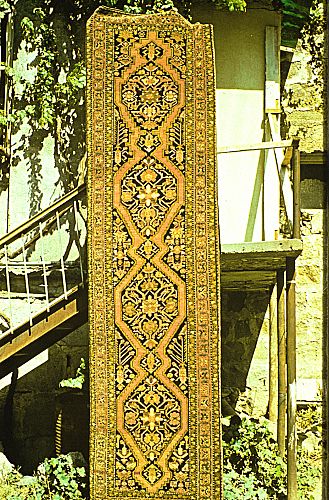

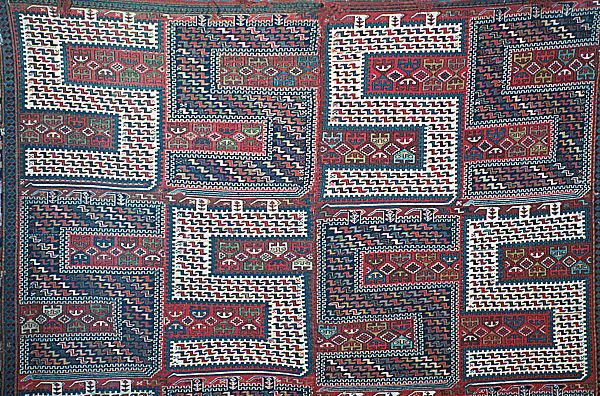

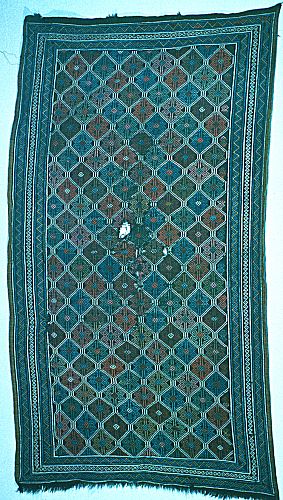

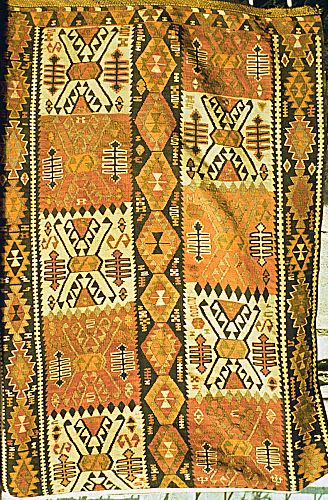

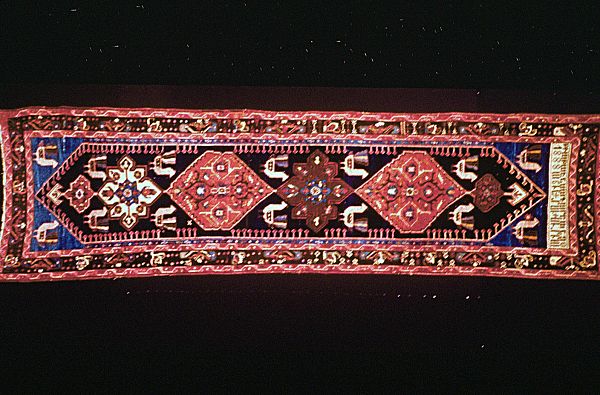

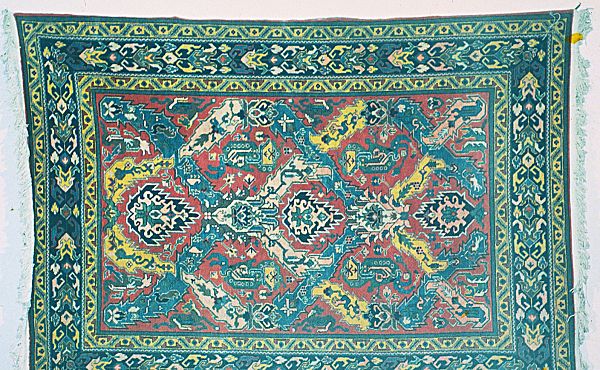

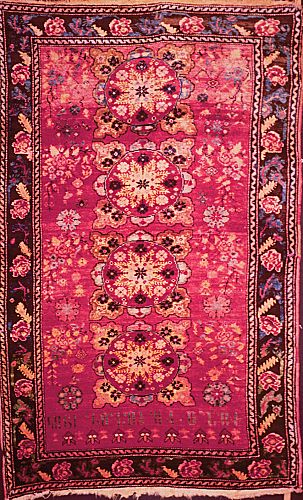

Armenian rugs, though woven in various regions and in divers styles, are predominantly of the Caucasian type with vivid colors and broad geometric designs; often small figures or animals are placed randomly in the border or field. The most frequently encountered types among the inscribed rugs are Karabagh (Artsakh) [222, 225, 226, 228, 233, 235, 238, 239], Kazak, and Gendje or Ganja [234]. The earlier Karabagh rugs with sunburst or eagle designs [224] seem to have affinities with the famous dragon carpets [221, 222] of an earlier period. Other Karabagh types are popular: Kasim Ushak design, cloudband design [227], jagged red band design, lempe/lampa design [233, 235], Lesghi star design, etc. Armenian Kazak rugs are classified by the following types: three medallion design, Lori-Pambak design, Sevan-Kazak design, Karachoph design, etc.

Among the most famous Karabagh carpets are a large number produced at the turn of the twentieth century with designs copied from western models [VI/18], which were in great vogue in the Caucasus and Iran. These fall in two large categories, the rose design rugs [218] and the pictorial rugs. There are also a large number of Karabagh, Kazak and village rugs with unique patterns as well as saddle bags or twin bags [240] from Artsakh.

Another type of pictorial rug was also woven by Armenians in the various parts of the world they settled in after 1915. These rugs, usually one of a kind, were woven by individuals to commemorate an event or to honor a person. Many of these have portraits of Soviet leaders -- Marx, Lenin, Stalin -- or western statesmen or historic symbols. Orphan rugs produced by young Armenian women, parentless survivors of the massacres of 1896 or 1915, under the guidance of American missionaries, are also numerous. To this day, the rug industry remains an important part of the organized crafts in Armenia

B. Woven and Stamped Textiles

Cloth weaving and textile manufacture is universal. Nearly all cultures engaged in this craft to satisfy need for clothes and coverings. Carbonized fragments of woven textiles have been found in very early excavations in Armenia, but they offer little information about the design and style of early textiles. The fragility of cloth is the major cause for our lack of early examples. The dry desert climate of Egypt or the frozen environment of the Scythian tombs of Pasyryk lacking in Armenia offers the very rare conditions by which early textiles have survived in quantity.

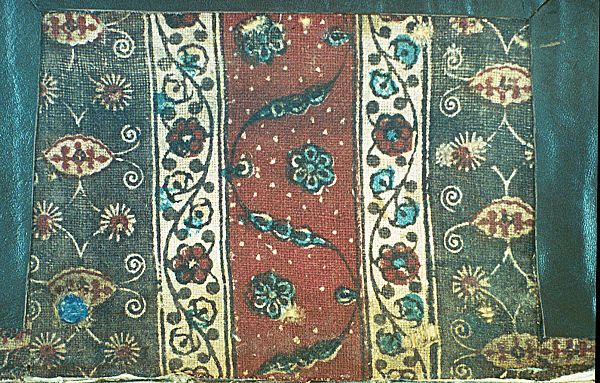

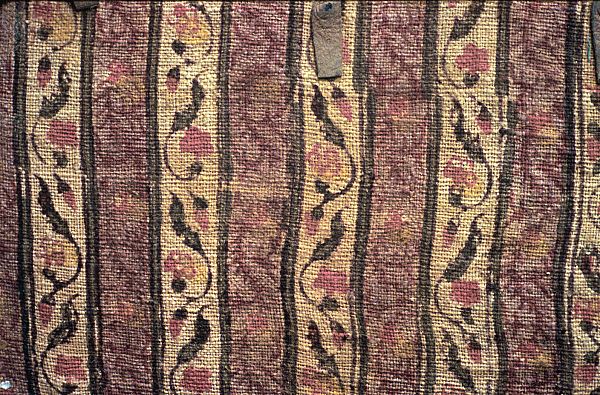

Our knowledge of pre-seventeenth century woven textiles stems mainly from their representation in art, sculptured reliefs such as those of Aght'amar [130, 131] and especially Armenian miniature painting [69, 79, 87, 89, 120], but also from actual fragments preserved on the insides of the covers of manuscript bindings [241, 242, 243, 244]. These textile fragments are made of various types of cotton, silk, linen and other fabrics and have both woven and stamped patterns. A large number of them are from cloth fashioned outside Armenia [243, 244]: Iran, India, even Byzantium and the west. Because nearly every manuscript up through the seventeenth century used such cloth pieces to hide the unattractive exposed wood on the inside of bindings [244], there are thousands of these textile samples preserved. Fewer than a hundred have been published. Once available, they will serve as the major resource in reconstructing the history of textiles used in Armenia from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries.

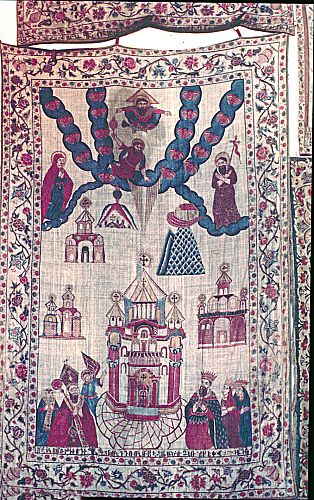

From the late seventeenth and especially the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there is preserved a comparatively large quantity of brocades, embroidery and other textiles almost all used as church decor or priestly vestments. The most important of these in size are the altar curtains [245, 246, 247], both stamped and embroidered, preserved in the collections of the Catholicossate in Etchmiadzin [246, 247] and the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem. Most of the eighteenth century examples are rich in color and form and were produced in Madras, India [246, 247], a major center of stamped fabrics, where Armenians were well established. These were made by stamping prepared cotton fabrics with carved wooden blocks [248]. This technique was also known in Armenia and used in earlier centuries, but in the later times Madras seemed to control the market. Though these large altar curtains had purely Armenian designs, often the life of St. Gregory [245] or the conversion of Armenian to Christianity [246], with long Armenian inscriptional bands, they were probably manufactured by Indian workers after designs supplied by Armenian artists.

Among printed or painted altar curtains, other than those produced in Madras, several are of a particular splendor: a stamped curtain from Souchava in Romania dated 1663 with a central motif of the Crucifixion and an upper band devoted to the life of Christ (Etchmiadzin Treasury); two others on dark blue cloth, probably made in Tokat, dated 1756 and the late eighteenth century with the Crucifixion as the most important representation (Etchmiadzin Treasury); others from Karin-Erzerum, Tiflis, Lim at Lake Van (felt appliqué), Constantinople (mostly embroidered), and Europe [245]. The Etchmiadzin collection has been the subject of a recent unpublished thesis in Armenian and the Jerusalem collection of altar curtains will soon be published.

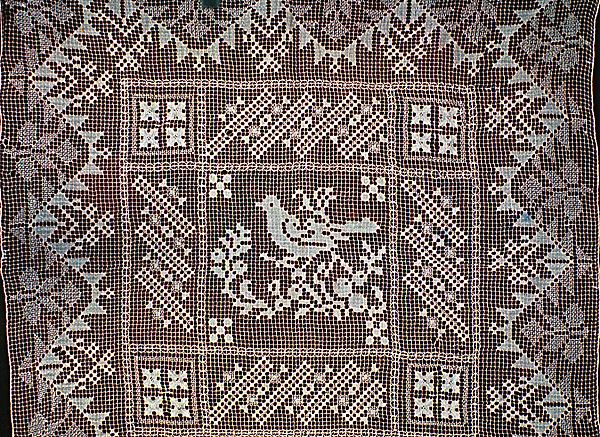

C. Needlework: Embroidery and Lace

Richly embroidered Armenian textiles have survived in much greater number than plain or printed fabrics. These embroideries are mostly church related: clerical robes [251, 252, 254] and accessories [254], altar curtains [245, 246, 247], chalice covers [255], and miscellany. Among the vestments are miters [254], crowns, copes [252], stoles, collars [251], belts [VI/33], sleeve bands [254], chasubles, and slippers. Major collections with pieces dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries are kept in the monasteries of Etchmiadzin [250, 251, 252, 254], Jerusalem, the Mekhitarists in Venice and Vienna [245], Bzommar in Lebanon and other lesser centers. Rich figural designs on silk, velvet [252], satins and more modest materials are sewn in vivid colors, the most lavish employ gold and silver thread [251, 252, 253, 254], pearls [251] and other precious and semi-precious stones.

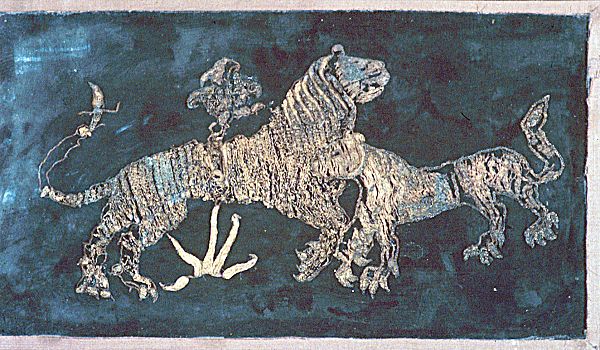

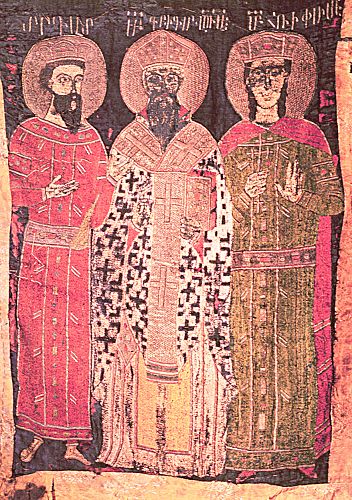

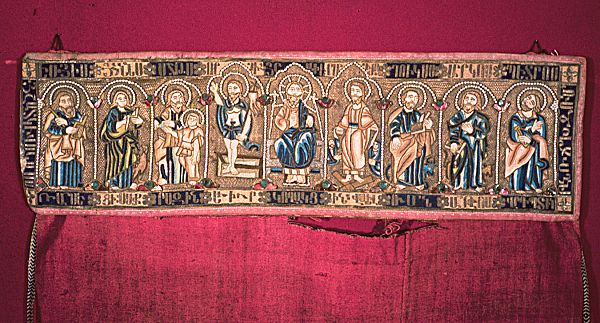

The variety of designs and styles are as astounding as they are beautiful. The perfection of execution, the rendering of figures, garments and faces [250, 251] is as magnificent as the best embroidery work of any period and any nation. The earliest surviving embroidery is a large thirteenth century fragment from Ani [249] showing asymmetrical lions. The most famous embroidery is the ceremonial banner of 1448 [250], still kept at Etchmiadzin, with full-length portraits of Gregory the Illuminator flanked by King Trdat and St. Hrip'simé, the major figures responsible for the Armenia conversion to Christianity on one side [250] and, on the other, Christ enthroned with the symbols of the four Evangelists.

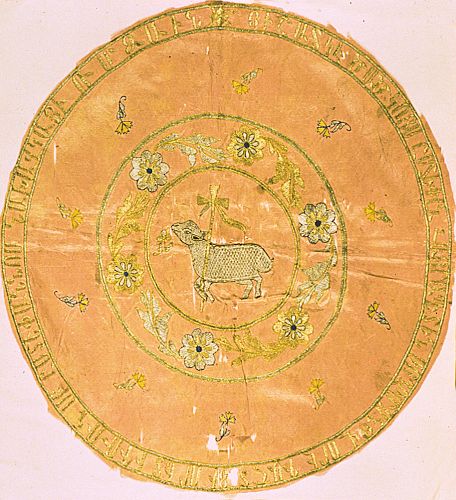

Among other outstanding embroideries one should note the following; the cope of 1601 in the State Historical Museum, Erevan, showing Christ enthroned with the Evangelists' symbols; a crown of 1651; a stole of 1736 and another on blue ground of 1685; a series of shirt collars in the form of short stoles dated 1734 all of embroidered silver and gold thread on a red ground, the most elaborate of which depicts the Last Supper on the back and John the Baptist, Gregory the Illuminator and St. Hakob on the front; embroidered altar cloths of 1613 from Karin-Erzerum with St. Gregory, of 1619 from Constantinople on a rich emerald colored ground with silver and gold thread showing the Virgin being presented with the martyred head of St. James (Hakob) with scenes from the Life of Christ in the borders (Jerusalem, Armenian Patriarchate), of 1620 from Constantinople with a monumental scene of the Last Supper bordered by Christological episodes (Jerusalem, Armenian Patriarchate), of 1704-1714 from Constantinople with Christ, the Apostles, St. Gregory and King Trdat, and of 1741 with St. Gregory's vision of Holy Etchmiadzin; the so-called eagle carpet of Catholicos Philippos dated 1651 using silver thread embroidery on silk; and the chalice cloth of 1688 with a central floral motif on a yellow ground with crosses and seraphim in the border. Except where noted, all the examples are in the Treasury at Holy Etchmiadzin.

Embroidery was commonly used to decorate towels [253], bags [257], stockings [258], kerchiefs, table clothes and various textiles [256, 257]. Among the most famous was the work of Marash characterized by polychrome geometric and floral designs on dark or colored backgrounds. The stitching was done following various grid patterns, designs being built up from star, cross and braided motifs. This embroidery work [255], whether of the luxurious variety or the more modest type, was done in all Armenian families, often during the isolation of the cold winter months. Many of the richly decorated elements of clerical garb were votive offerings donated by the pious on pilgrimage.

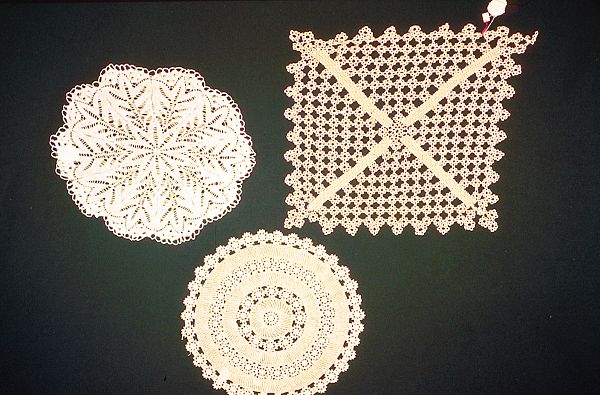

Armenian lace [259, 260], called janyak or oya, is executed with a single needle and has an extremely ancient history. Its technique was known by all women and passed on from generation to generation. There are different styles and stitches from the various regions of Armenian; among the best known are the Aintab stitch, the Vaspurakan stitch [260], the Baghesh (Bitlis) stitch and the Kharpert stitch. The delicacy and intricacy of Armenian lace have long been recognized and in recent years specialized studies and exhibits have been devoted to it. Early laces of silk and gold thread or decorated with pearls and jewels were made into chalice covers, and cross and Gospel holders. Lace borders were also often added to embroidered articles. Scarves and kerchiefs were often fringed with a variety of miniature lace flowers.

Few pre-nineteenth century laces have survived. The tradition, however, is very ancient in Armenia. Lace making in Europe was a craft that arrived in the late Middle Ages from Asia Minor. Many scholars believe that the origin of Venetian lace, one of the oldest and most developed lace making centers, should be sought in Armenia. The merchant cities of Italy were in close touch with Armenians during those centuries, so there was ample opportunity to import laces and the technique of making them.

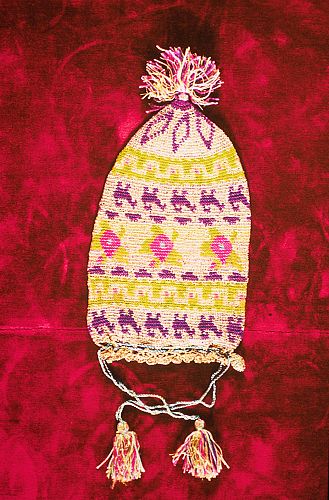

D. Costumes

The oldest existing Armenian costume is a rather plain thirteenth century child's dress found at Ani, but it is the unique piece we have until the seventeenth century. Liturgical garments are preserved from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries [251, 252, 254], but almost no secular examples exist. Nineteenth century garments are, however, plentiful and from them scholars have been able to establish the daily as well as special costumes of Armenian men and women from every region of Armenia. This material has been published in special albums and exhibited in museums in Armenia and the diaspora. Our notion of earlier costumes of the ancient and medieval Armenian periods is based entirely on representations in Armenian art, especially manuscript illustrations.

Serpent carpet...