College of Arts and Humanities

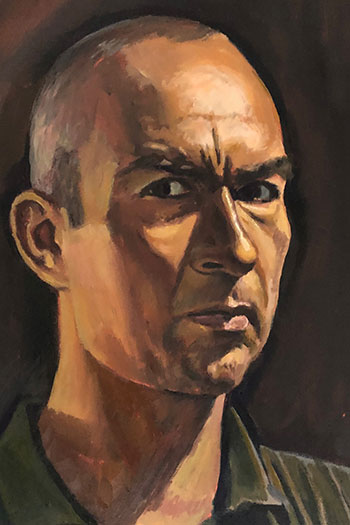

Nick Potter

Professor

Art, Design, and Art History | 559 278 4731 | Office: CA273

Education

- BA Cheltenham College of Art

- MFA Birmingham School of Art

Courses Taught

Nick was born and raised in London, England. Much of the artwork he produced there was fueled by the banality of everyday spaces, particularly the elevators, lobbies and corridors of tower blocks and public spaces.

After completing graduate studies at the Birmingham Art Institute, Nick moved to the U.S in 1999, where he taught at Florida State University for two years before moving to California.

His current works reflect on modernist architectural spaces, images of power, class and materialism that represent fears about existence and isolation. His seductive depictions of artificial utopias, create tension and anxiety that remind us of the foreboding doubt that lingers only slightly below the surface of our desires.

ARTIST STATEMENT:

It can be argued that the greatest examples of any culture’s architecture reflect its ideologies and values. Whether Roman, Renaissance, Modernist, Soviet, or Fascist, the architecture is a form of propaganda, a pseudo-utopia, idealized and often highly seductive.

The architectural scenarios I have created may at first be interpreted as symbols of success; on the surface we see an appealing, perfected, modernist world. But as one contemplates the ideal further, we become aware that something isn’t quite right, we experience a mix of futuristic dread and excitement where dystopia and utopia converge. Is this an abandoned world? And why? I want the viewer to experience a shift from utopian to dystopian in a similar way to how one realizes a dream has just started to become troubling while still aware that the reasons for the change are yet to be revealed.

I have been inspired by visits to Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings in Brazil, my ongoing obsession with Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation buildings, and the futuristic dystopian scenarios within the fiction of J.G. Ballard. I focus on the modernistic richness of the architectural elements (unattainable for most) while evoking the implication of a dystopian narrative that could be the result of climate change or political upheaval.

NICK POTTER’S CONSTRUCTED UTOPIAS QUESTION MODERNISM’S ALLURE

U.K.- born Nick Potter has rendered a world not in sci-fi tropes with flying cars and plagued with technological missteps and incessant climate-induced acid rain, but an even more deflating present-day Modernist noir, rooted less in fantasy than in convincing realism.

Text by Aaron Collins

For Lifestyle Magazine – December 15, 2019

Looking at Fresno-based Nick Potter’s mildly dystopian paintings on view in his first one-person show at the Fresno Art Museum in November, one might recall that this milestone was the setting for Ridley Scott’s futuristic Bladerunner (1982). But unlike in the acclaimed Philip K. Dick-inspired film, U.K.-born Potter has rendered a world not in sci-fi tropes with flying cars and plagued with technological missteps and incessant climate-induced acid rain, but an even more deflating present-day Modernist noir, rooted less in fantasy than in convincing realism. Utopia wasn’t so great after all.

Potter’s vision is replete with unfulfilled longings like those found in Edward Hopper’s pre-war trademark works, with their yearnings and isolation. Noted Hong Kong-based photographer Michael Wolf’s engulfing, overbearing modernism comes to mind, sharing a culprit in common with their towering structures obliterating sun and sky. But Potter makes a vaguely guilty pleasure of his Miesian fetish. He echoes Hopper’s pre-war emotional stance, but extends it beyond into post-WWII ennui, questioning Modern architecture’s role in our contemporary malaise, questioning how well Modernism’s gambit panned out.

The works in Nick Potter: Constructed Utopias function in a similarly dislocating if more subtle way as Scott’s unsettling cinematic masterpiece, with its (then-somewhat atypical for sci-fi) agglomerated historical styles and accumulated grit. Comparatively, Potter’s world is more pristine and closer to home, even as it reflects our times in which we are seemingly on the verge of one disaster or another.

Modernism may have flourished in the present age, enjoying a resurgence

in the oughts with its bright pristine Instagrammable surfaces, whose 20th-century predecessors may have aged well enough (if not its various theoretical certitudes). However, in Potter’s slightly foreboding canvases, it is an architecture that has seemingly alienated — not enlivened — its intended occupants. Structures are plucked from context and placed on plinths like specimens in works like Differing Fading Systems (2016) with its provocative reflection, and Order and Progress (2019), both which invite viewers to examine them in isolation as if quarantined, pathogens at risk of infecting their surroundings.

Potter’s works function like cinematic sets in their own right, akin to the ’80s psychodramas of David Salle and Eric Fischl (whose work Potter often teaches about as an art professor at California State University Fresno). While Potter clearly has love for the Modernist style, his oil paintings are often devoid of human presence and, to some extent, narrative — leaving one to ponder whether these venues’ disappointments were perhaps rooted in human folly, earnest but ultimately failed attempts that have been found unworthy, not uninhabited momentarily but perhaps permanently. Their simmering unease is palpable, but the causes are wisely left to the viewer’s instincts. Here in Potter World, ambiguity reigns.

Some of Potter’s works directly recall David Hockney’s ’60s-era good life Southern California paintings, with their swimming pools and view properties rendered as optimistically as any art of the period (“advertisements for California,” the younger Brit says). Hockney is an acknowledged influence on Potter. But while Hockney’s stance can be seen as a deliberately cheery contradiction to that era’s social unrest, Potter’s nocturnal settings bear the tensions of the present, albeit obliquely. Like Hockney, he courts the same voyeuristic quality, that of peering into a privileged world. If Hockney revels as the quintessential bon vivant, Potter portrays a sober, grimmer outlook in synch with our own particularly grim times.

“I looked at (Hockney’s) work a lot when I was at college, and although my work was far from anything similar to his in those days, I found his portraiture really interesting, ranging from his working-class parents to those living in luxury, like Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy, which feels like a modern day version of Gainsborough,” Potter said. “But one thing that stuck with me more than anything regarding his work over the years were the California swimming pool and art collector portrait paintings. Hockney’s California work feels like an advertisement for the American Dream, for modernist architecture.